In this week’s post we look at some of the technology for monitoring wildlife, especially birds. We hope to send out a similar post later with an emphasis on native plants. We will attempt to show how multiple levels of technology are interconnected. How are our smartphone apps related to the study of climate change and how do they support efforts to increase climate resilience?

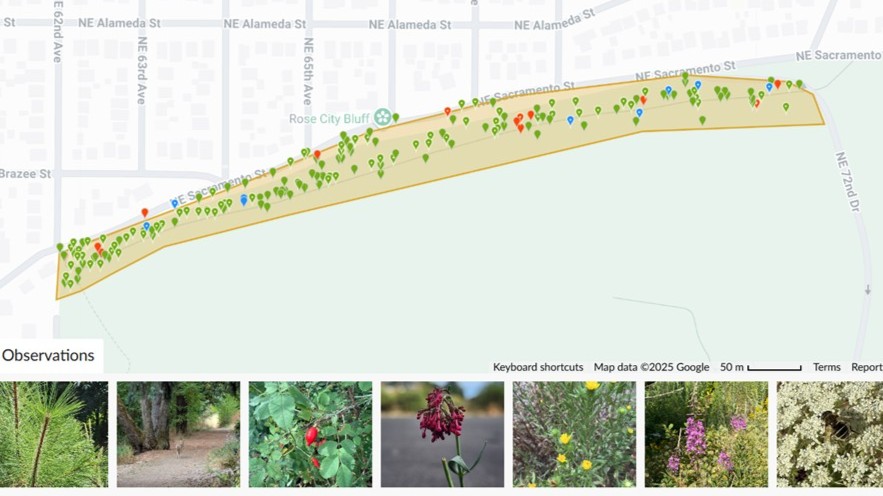

Hardware, Smartphones: At the most basic level we now have powerful hardware in the hands of everyday users. Many of us are familiar with Merlin for identifying birds by sound using a smartphone microphone, or PlantNet (aka Pl@ntNet) for identifying plants using a smartphone camera. Rose City Bluff Restoration hosts an iNaturalist project for the Bluff. To date 43 observers have made 275 observations of 119 species of plants and animals on the Bluff. Each of these apps use the smartphone’s GPS system as well as the camera and microphone.

BirdWeather: We recently became aware of a portable device, the BirdWeather PUC ($259), for monitoring bird songs. Typically, you set it up to listen for birds continuously, at your house or perhaps a habitat under study. While it uses acoustic detection technology like the Merlin app, BirdWeather focuses on continuous data collection and environmental monitoring. You can connect your BirdWeather PUC to your home Wi-Fi, and it will monitor the sounds at your home, identifying bird songs in real-time. You can share sounds on a global map. You can also take the device with you on a hike or on vacation. Since 2021, BirdWeather PUCs have heard 4,560 distinct species vocalize 1.6 billion times across 12 thousand locations.

Applications, Merlin: The next level up from hardware are end user applications like Merlin and eBird. The Merlin app’s primary function is to identify birds through step-by-step questions, photo analysis, or sound recognition.

eBird: While Merlin helps birders with identification, eBird is a platform for reporting and tracking bird sightings, allowing users to create life lists, view data from other birders at specific locations, and contribute to a global scientific database of bird observations. Use Merlin to help identify a bird, then add the species to your eBird list. It’s ideal for serious birding, keeping detailed records, and contributing to scientific data on bird populations. RCBR volunteer Trask has used eBird to document 100-plus bird species on the Rose City Golf Course and the Bluff.

eBird serves as a global database of bird observations. Merlin uses this data to help users identify birds in the field. Merlin relies on eBird’s extensive dataset for its bird identification features, and users can enhance Merlin’s functionality and contribute to the database by submitting their own sightings and recordings to eBird.

Data, BirdNET: A level up from end user applications we have data collection and analysis projects. Both Merlin and eBird are connected to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s shared data infrastructure, BirdNET.

BirdNET is a research platform that aims at recognizing birds by sound at scale. BirdNET is a citizen science platform as well as an analysis software for extremely large collections of audio recordings. BirdNET can currently identify around 3,000 of the world’s most common species. The BirdNET app lets you record a file using a smartphone and will find the most probable bird species in your recording. The app uses the sound recording feature of smartphones as well as GPS to make predictions based on location and date.

eBird data contributes to the BirdNET project by providing information on bird distribution and occurrence. User-submitted sound recordings from Merlin help train and improve BirdNET’s artificial intelligence models.

BirdWeather uses BirdNET to process audio from the PUCs. BirdNET was developed as a joint project by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Chemnitz University of Technology. The Cornell Lab contributes to BirdNET’s research and development.

Ultimately much of the data from our end user applications and from research platforms like BirdNET is fed to global data archives used for research. eBird is a data collection platform, BirdNET is a mobile app for bird sound identification using AI, and the Macaulay Library is the permanent digital archive for bird media (photos, audio, video) that powers many Cornell Lab of Ornithology projects, including Merlin.

iNaturalist: iNaturalist helps with bird identification by allowing you to upload photos or sound recordings of an observed bird, which then uses AI to suggest identifications. (iNaturalist is not bird specific.) You can also get help from the iNaturalist community of users, who can provide feedback, offer their own identifications, or confirm the identification to make it “research grade”. iNaturalist does not use the Macaulay Library, but they are both major archives of biodiversity data that contribute to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), making their data available for global biodiversity monitoring.

Macaulay Library: The Macaulay Library is the world’s largest scientific archive of animal recordings, including a vast collection of bird sounds, housed at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. It collects and preserves recordings of animal sounds and behaviors from around the globe, providing valuable scientific data for researchers, educators, and conservationists. The Macaulay Library offers a library of over two million sound recordings and tens of millions of photos and videos of birds and other wildlife. The recordings come from all over the world, capturing variations in sounds across distinct species, regions, and time. Each recording includes valuable information such as the species, date, time, location, and even the behavioral context of the sound. The Macaulay Library contributes to GBIF, with its data being a significant source of audio and visual biodiversity information shared through the GBIF network.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF): GBIF is an international organization that focuses on making scientific data on biodiversity available via web services. A wide range of institutions globally provide data, which users can efficiently access and search through GBIF. GBIF sources data from a vast, international network of publishers who contribute biodiversity data, including museum specimens, citizen observations, camera trap images, and ecological surveys. The GBIF data includes distribution of plants, animals, fungi, and microbes. The mission of the GBIF is to facilitate open access to biodiversity data worldwide to underpin climate resilience.

We hope this helps us understand how our smartphones contribute to efforts of scientists to improve climate resilience. We know many of you are more knowledgeable about this topic than we are – we invite you to leave comments on this blog.